Guest Post: Paul Krugman’s Mis-Characterization Of The Gold Standard

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 08/30/2012 20:42 -0400

Submitted by James E. Miller of the Ludwig von Mises Institute of Canada,

With a price hovering around $1,600 an ounce and the prospect of “additional monetary accommodation” hinted to in the

latest meeting of the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee,

gold is once again becoming a hot topic of discussion.

George Soros

made news recently

when a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission revealed that

he had liquidated his position with major financial firms and had

loaded up on gold; approximately 884,000 shares worth. Jim Cramer, the

CNBC personality in constant search of growing business trends,

recommends putting at least 20% of one’s assets in gold. Following the Republican National Convention, the

party platform now proposes the establishment of a commission to study “the feasibility of a metallic basis for U.S. currency.”

Like the gold commission before it, this new interest in gold has

brought out the critics who regard the precious metal as nothing short

of, to borrow the infamous term coined by

John M. Keynes, a “barbarous relic.” Wesleyan University economist Richard Grossman writes in the

Los Angeles Times that the idea of a gold commission is a “waste of time and money” because the standard hasn’t “worked for 100 years.” In

The Atlantic, fiat currency enthusiast Matthew O’Brien calls the

gold standard a “terrible idea” and presents a few charts demonstrating that linking the dollar to gold failed to keep prices stable.

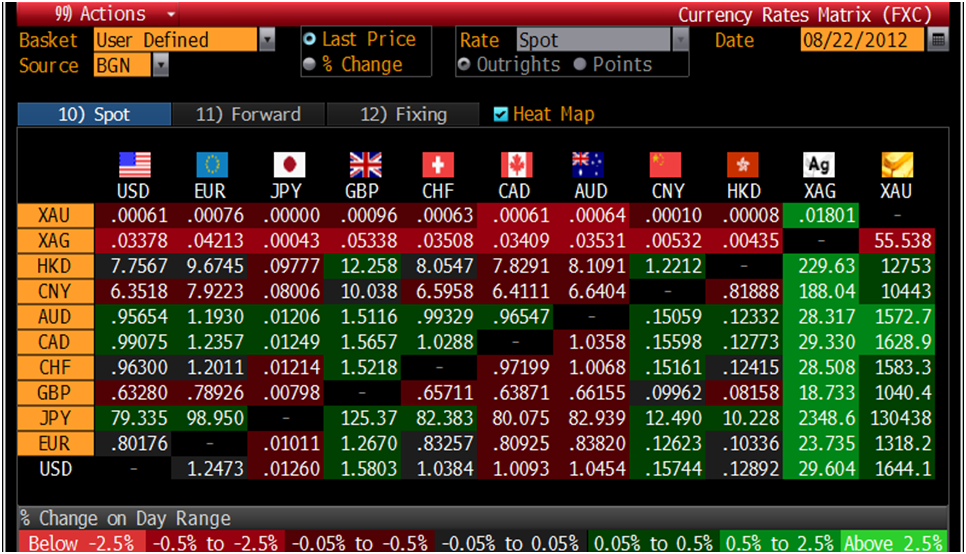

Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman has praised O’Brien’s article on his blog and makes sure to point out that the price of gold has been highly volatile since 1968 by showing the following chart:

There is a remarkably widespread view

that at least gold has had stable purchasing power. But nothing could be

further from the truth.

Krugman points out that when interest rates are low the price of gold typically rises.

He claims that as interest rates tend to fall during recessions, gold’s

rise in price would lead to “a fall in the general price level.”

Lastly,

Krugman ridicules the notion that a true gold standard

would prevent asset bubbles and subsequent busts from occurring by

calling attention to the fact that America suffered from financial

panics “in 1873, 1884, 1890, 1893, 1907, 1930, 1931, 1932, and 1933.”

These criticisms, while containing empirical data, are grossly deceptive.

The information provided doesn’t support Krugman’s assertions

whatsoever. Instead of utilizing sound economic theory as an

interpreter of the data, Krugman and his Keynesian colleagues use it to

prove their claims. Their methodological positivism has lead them to

fallacious conclusions which just so happen to support their favored

policies of state domination over money. The reality is that not only

has gold held its value over time, those panics which Krugman refers to

occurred because of government intervention; not the gold standard.

Right off the bat, the Nobel Laureate makes the amateur mistake of conflating two different gold standards.

There was not one set standard throughout the 19th century up to the

Great Depression. Until the first World War, the United States and much

of the West was under the

classical gold standard.

This meant that the dollar was just a name for a set amount of gold;

generally 1/20 of an ounce. Following the massive inflation used to pay

for World War I and the Genoa Conference of 1922, the

gold exchange standard

was adopted by many Western countries including Britain. Though the

United States remained under an imperfect classical gold standard, other

Western countries stopped redeeming gold coins for national

currencies. Instead, they redeemed their currencies for dollars or

pounds which allowed for expanded fiscal policies because the constraint

of gold was not so prominent. At the same time, President of the New

York Federal Reserve, Benjamin Strong, conspired with the head of the

Bank of England, Montague Norman, to keep gold from flowing out of

Britain by having the Fed adopt “easy money conditions in the United

States” and “increase bank liquidity a great deal”

according to

economic historian Robert Higgs. This backroom deal was carried out as

England readopted the gold standard in 1926 at the pre-World War 1

parity despite the pound being devalued during the war. Because trade

unions and unemployment insurance made wage rates less flexible

downwards, the ensuing deflation was detrimental and combated through

further inflation aided and abetted by the Fed.

This new international agreement between central bankers may

have appeared to be a maintaining of the classical gold standard but it

was nothing of the sort. The inflationary boom in the later

half of the 1920s was a product of the monetary scheming of the Fed and

Bank of England. The final result was the stock market crash of 1929

which ushered in the Great Depression. Contrary to popular belief, the

Depression was not caused by the classical gold standard but because of

its rejection.

As for the other panics Krugman mentions, neither were caused

by the gold standard but by government intervention in the money market. As economist Joseph Salerno

explains, the pervasiveness of

fractional reserve banking,

or the expansion of credit unbacked by gold reserves, played a key role

in creating financial instability. The panics were caused primarily by

..the establishment of a quasi-central

banking cartel among seven privileged New York banks resulting in the

almost complete centralization of U.S. gold reserves in their vaults by

the National Bank acts of 1863-1864. This New York City banking cartel

was able to expand willy nilly the monetary base and the overall money

supply by expanding their own notes and deposits on top of gold

reserves. Their notes and deposits were then used as reserves by lower

tier banks (Reserve City Banks and Country Banks) on which to pyramid

their own notes and deposits.

Moreover, banks, especially the larger

ones, were encouraged in their inflationary credit creation by the

firmly entrenched expectation that they would be freed from fulfilling

their contractual obligations in times of difficulty by the legal

suspensions of cash payments to their depositors and note-holders that

recurred during panics throughout the 19th century.

In sum, an adherence to a real gold standard was not the main cause of all the financial panics Paul Krugman lists.

It was his favorite institution, the state, and the incessant fiddling

around with the economy by the political class that created an unstable

monetary system. It is also worth pointing out that the late 19th

century was a period of incredible economic growth for both the United

States and the rest of the world in spite of the flawed gold standard.

Though it is often alluded to as a time of robber barons, worker

starvation, and terrible deflation, the U.S. economy experienced its

highest rate of growth ever recorded as the 1800s drew to a close. As

Murray Rothbard documents in

The History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II:

The record of 1879–1896 was very similar

to the first stage of the alleged great depression from 1873 to 1879.

Once again, we had a phenomenal expansion of American industry,

production, and real output per head. Real reproducible, tangible wealth

per capita rose at the decadal peak in American history in the 1880s,

at 3.8 percent per annum. Real net national product rose at the rate of

3.7 percent per year from 1879 to 1897, while per-capita net national

product increased by 1.5 percent per year…

Both consumer prices and nominal wages

fell by about 30 percent during the last decade of greenbacks. But from

1879–1889, while prices kept falling, wages rose 23 percent. So real

wages, after taking inflation—or the lack of it—into effect, soared.

No decade before or since produced such a sustainable rise in real wages.

From 1869 to 1879 the total number of

business establishments barely rose, but the next decade saw a

39.4-percent increase. Nor surprisingly, a decade of falling prices,

rising real income, and lucrative interest returns made for tremendous

capital investment, ensuring future gains in productivity.

When the United States maintained a gold standard to a fairly significant degree, the economy blossomed.

The relative absence of inflation ensured that the dollar acted as a

store of value in addition to facilitating transactions. Without the

threat of looming price increases, the public was more willing to put

off consumption and add to the supply of capital availability by

saving. The prudent technique of producing more than you consume

allowed for a greater number of entrepreneurs to put capital to work.

This set the foundation for mass production and giving consumers access

to an abundance of goods never thought possible just a century before.

To the Keynesians’ befuddlement, the economic renaissance of

the late 19th century occurred at a time where prices weren’t rising or

stable but actually falling. The fall in the general price

level occurred as the production capacity expanded at a faster rate than

the money supply. Today, economists of the Keynesian and monetarist

school remain convinced that a stable price level is good thing when

common sense dictates otherwise. Falling prices are a godsend for

consumers; not a catastrophe. As long as entrepreneurs are able to

utilize the inherent feedback mechanism of an undistorted pricing system

to forecast input costs, falling prices are only a minor problem. The

focus on price stability is why many economists

missed the Depression and the Fed-engineered boom of the 1920s. In a free market, the tendency is for prices to fall as production increases.

Krugman denies not only that sound money leads to economic

stability and growth, he does so while attempting to show that gold has

been incredibly volatile since Richard Nixon cuts the dollar’s tie to

the precious metal in 1971. But Krugman puts the proverbial

cart before the horse with his example as it hasn’t been the price of

gold that has fluctuated to a high degree but rather the dollar’s

value. As

Forbes editor John Tamny

pointed out in August of 2011

as Brookes calculated in his essential book The Economy In Mind,

“In 1970 an ounce of gold ($35) would buy 15 barrels of OPEC oil

($2.30/bbl). In May 1981 an ounce of gold ($480) still bought 15 barrels

of Saudi oil ($32/bbl).” Fast forward to the present, and an ounce of

gold ($1750) buys roughly 20 barrels of oil ($85)

Krugman also asserts that when interest rates fall, the price of gold increases [ZH - we discussed the various regime changes between interest rates and gold here in great detail].

But again he makes the same mistake of not recognizing the role dollar

manipulation plays in both measures. Interest rates haven’t been formed

by market forces since the Federal Reserve was established. In a free

market, interest rates are determined by the public’s collective time

preference or the discounting of future goods against present goods.

When more people are saving, and therefore putting off consumption,

there is a higher supply of loanable funds. This higher supply

translates to lower interest rates as the price of present capital

lowers. Under a fiat regime like the Fed which oversees a system of

fractional reserve banking, interests rates are manipulated by a few

central bankers instead of the market. These central planners increase

the supply of money in an effort to push down interest rates and induce

consumers into borrowing. This also has the effect of pushing up the

price of gold as investors lose confidence in the dollar’s value.

In his crusade to keep Keynesianism as a legitimate school of

thought, Krugman has yet again attempted to mischaracterize gold and

blame it for crises caused solely by government intervention. What Keynesianism amounts to is a theory of state worship and the virtue of hedonism. Its leading proponents declare

there is such thing as a free lunch

and that it is served directly by the printing of money. In other

words, it is based on backwards logic and remains distant from reality.

The Keynesians admit there was a housing bubble then fret over an “output gap.”

They blame market exuberance for recessions but then prescribe the

exact same policies that lead to exuberance to begin with. This

irrationality was best displayed with a remarkable quote by former

Treasury Secretary and former director of President Obama’s National

Economic Council Lawrence Summers who wrote in an

editorial for the Washington Post:

The central irony of a financial crisis

is that while it is caused by too much confidence, borrowing and

lending, and spending, it can be resolved only with more confidence,

borrowing and lending, and spending.

Keynesians have no pure economic theory; they are totally ad hoc in their approach.

Any data point which fits their view is trumpeted. Any theory that

presents a challenge to the idea that the economy can be finely tuned

like a child’s trinket is dismissed as right-wing propaganda.

Keynesians ultimately reject the golden rule of economics: savings

represents deferred consumption and producing more than is consumed.

Real savings in the form of capital goods (factories, equipment,

machinery, etc.) are the backbone of any economy. Government only

squanders these scarce resources through its constant pillaging of

wealth.

Keynes himself was contemptuous of the middle class throughout his professional career. This is perhaps why he held such disdain for gold.

Gold is the market’s choice for money; not the statist ruling class

dependent on spending virtually unlimited sums of tax dollars. Because a

true gold standard prevents runaway inflation and budget deficits from

occurring in perpetuity, Keynesians will do all they can to discredit

gold as a workable form of currency. Their allegiance lies with the

state and paper money; not the natural choices of the common man.